It’s hard to sell insurance. If you’re in the insurance industry, that’s something you probably already know. It’s hard to buy insurance. If you’re a consumer of insurance, that’s something you almost definitely know.

Whether you’re on the selling side or the buying side of the insurance equation, there are a lot of reasons why it’s a difficult transaction to conduct. But here’s something you may not have considered: Many of the reasons insurance buyers and sellers don’t connect are driven by the way our minds process risk.

A Tough Buying Process

The insurance industry makes it hard. Insurance jargon is hard for many consumers to understand. Consumers encounter words that show up in insurance contract language that virtually never appear in any other application of the English language. Or, they’ll see words that are common in English but have meanings that are unique to the insurance contract context. The language of insurance is tough to decipher, which is why there are so many insurance dictionaries and glossaries. As it turns out, we need all these words to describe the infinite range of insurance products and their attributes. Surely, another problem with insurance is the paradox of choice – too many companies offering too many choices without enough differentiation among them.

As if that weren’t tough enough for beleaguered consumers, they shouldn’t expect price transparency from this industry, either. With most insurance purchases, the consumer doesn’t see the final price until after the collection of a lot of very personal information, some of it in the form of bodily fluids. And after all that, sometimes there is no sale at any price, and the application is declined.

And then there is regulation…another story for another day.

Cognitive Biases

Not all the problems are self-inflicted. There are cognitive and behavioral biases pre-wired into the brains of consumers, and some of these biases make it hard to sell insurance. I recently found this list of over one hundred biases that describe the irrational or odd behaviors that can occur at the intersection of psychology and finance.

The biases exist because of how the mind works. An important thing to understand about how the mind works is that it has two systems of thought, according to Daniel Kahneman, a renowned psychologist known for his work on judgment, decision-making, and behavioral economics. I’d like to relay a slice of what this Senior Scholar at Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs has written in his excellent book, Thinking, Fast and Slow.

So, back to the two systems. System 1 thinks fast. It’s always on, looking for patterns and finding them. It answers questions; If it doesn’t know the answer it will make up a different, related question that it can answer. But sometimes it makes mistakes.

Then there is System 2. It thinks slow. It is analytical and reflective. It tells stories. Sometimes it will stop System 1 to analyze a problem, which is good. But…

System 2 has capacity limitations. It can’t review all of System 1’s conclusions. When it does engage, it will tell a story about what it finds, and sometimes the stories support the incorrect conclusions or justify taking the wrong shortcut identified by System 1. So, Systems 1 and 2 work very well together most of the time, but even working together they sometimes make mistakes.

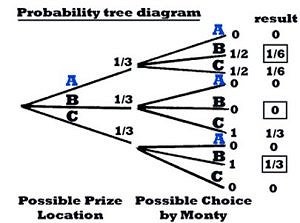

Let’s apply this model to buying insurance. Our minds are prone to make mistakes when judging probability and assessing risk. Shown in Figure 1 we have a probability tree – this one happens to be related to the Monty Hall problem – number 73 from that list I mentioned previously. For readers under a certain age who are unfamiliar with this reference, Monty Hall hosted a 1970’s game show called Let’s Make a Deal that asked contestants to select from three choices to win a prize behind a door. It involved wide collars, funny costumes, and, perhaps, math. After a contestant had made a selection (A, B, or C), sometimes they were given a second chance to switch—before any door was opened. (Sometimes they opened the door immediately after the first pick to reveal…a goat?)

Even though it seems as if the contestant has a one in three chance of winning, the outcome could be manipulated by the host. It’s not one in three because as one game theorist concludes, “the possibilities are not sufficiently narrowed for there to be a unique solution.” Even a relatively simple probability tree gets complicated quickly, especially when the game show host can introduce uncertainty. System 1 goes for a one in three chance, but System 2 second guesses, and can’t process all the probabilities.

Figure 1.

Consider Figure 2, an illustration of Prospect Theory demonstrating risk aversion. Here, when human emotions like regret and disappointment are introduced into the decision-making process, we see an asymmetrical curve like the one in the prospect theory diagram. Note the disparity of the amount of perceived pain generated by the loss of $50. Compare it to the amount of perceived joy gained by $50. It’s the same bill that bears Ulysses S. Grant’s face, but its loss is more keenly felt. So, the takeaway here is that people are prone to misjudge probability and they have an aversion to risk.

Figure 2.

Brains Are Bad at Insurance

Given that insurance essentially puts a price on risk based on the probability that something bad might happen, and that people tend to misjudge probability and avoid risk, you would think that would play right into the hands of insurance marketers. And you would be wrong…

This is because the risk aversion becomes risk-seeking in some scenarios. For example, when one choice is a sure loss, and the other choice is a greater loss, but one that is not certain to happen, then people tend to take their chances. They do not accept the sure loss that is small, in the hope that the greater loss will not occur.

So, what would that look like in real life? Well, it might be presented as a sure “loss” of, say $1,132 versus a loss of, say $39,800 that is only 0.38% likely to happen. But for banks that hold their mortgages, people would likely prefer to keep the $1,132 in their pockets and hope that the $39,800 of fire damages they could have insured for happens to someone else (http://www.iii.org/fact-statistic/homeowners-and-renters-insurance).

Conclusion: There’s a Joke in There, Somewhere

In summary, insurers and their agents are trying to sell a product that prospective buyers are pre-wired not to buy. There are also too many confusing choices and hurdles that make it difficult to purchase. So, what can be done?

First and foremost, insurance marketers could offer simplified choices, greater transparency in pricing, and a simpler buying process. But why bother with that when there’s still that wiring problem? What can be done about that?

As much as we might like to, we can’t just go in and change the wiring. But, we can understand better how it works and tools like fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) can help us. This brain-mapping technology lets researchers know where something happens in the brain. It gets us a lot closer to understanding why it’s happening, and helps separate real response from claimed response. Besides, Let’s Make a Deal contestants couldn’t look any weirder by wearing brain sensors on their heads.

So, if we can get a neuroscientist, a behavioral economist, and an actuary together in a lab to study the neuroscience of individual insurance buying decisions, we might be able to avoid some to the cognitive and behavioral biases. Products could be designed to be easier for the mind to understand, and have better roadmaps to navigate them. And that would help people make better decisions about the risks they are trying to insure.

Questions about buying or selling insurance to your groups? Contact us to learn more.